Managing risks on large complex projects

PART 3: Elements of Project Risk Maturity (PRIMA)

In the first two parts of this series, we looked at how to assess the level of the overall challenge and how the challenge level may vary over time. Here, we’ll go deeper on the levels of project risk maturity and how you can achieve the appropriate level to succeed.

We’ll stay with the Covid vaccine rollout in the UK as a large complex project we can all relate to. When the pandemic hit, the UK government was criticized for its ineffective approach to managing the spread of the virus. Lockdowns happened later rather than sooner; mask-wearing was initially considered ineffectual; the supply of protective equipment (PPE) was woefully inadequate; and the programme to ‘track and trace’ simply didn’t work.

Despite clear warnings that a pandemic was just around the corner, few governments had been expecting to have to tackle this problem on their watch. But the UK did worse than many other countries, even though Italy provided a frightening preview of what was coming. Rather than rising to the challenge, though, the UK seemed to be hoping the train hurtling towards its station might somehow pass through and derail somewhere else. By the time it became clear that a trainwreck was inevitable, mitigation efforts weren’t enough to prevent a high death toll. Instead, the only real hope for a return to normality was the development and distribution of a vaccine.

As I write, however, there’s been a change in fortunes. The UK seems to be outperforming its EU peers in the rollout of the vaccine. What’s happened? As noted before, we have nothing to do with the project and no information beyond media reports. But we can make some assumptions and use them to illustrate our own approach to project risk maturity.

‘Failure is not an option’

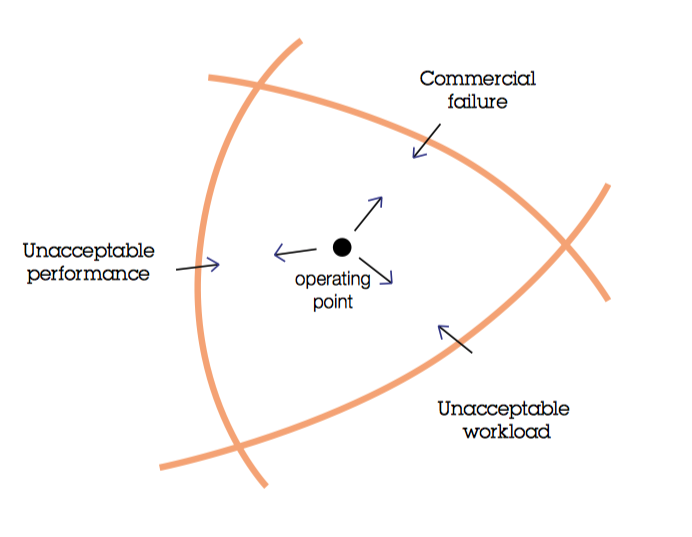

What does project failure mean? In the famous Apollo 13 space flight, the mission to land on the moon was aborted. When NASA flight director Gene Kranz said ‘failure is not an option’, failure meant the three astronauts not making it back to earth. The goal of the project itself had already failed. But failure is often less clear on large complex projects. Does failure mean an accident leading to loss of life? Or simply a blown budget, or an outcome that doesn’t deliver to the promised spec? We find Jens Rasmussen’s definition of three key failure boundaries helpful.

Any project always has an operating point in flux. In the for-profit world, there’s always commercial pressure that can push teams over the boundary of workload or acceptable performance.

Diagram of Failure Boundaries

In the case of the vaccine rollout, it may seem that a commercial boundary doesn’t exist; governments will throw whatever money it takes at the project. But perhaps we can see the ‘commercial failure’ boundary as a ‘political failure’ boundary. That is, governments will pressure other stakeholders in the project to deliver in the timescales they have promised the populace.

The ‘workload failure’ boundary is clear. The NHS has been put under enormous pressure, with nurses, GPs and other healthcare frontline workers all being asked to go above and beyond the call of duty. The ‘acceptable performance’ for vaccine delivery would take in regulatory, ethical, and legal considerations, as well as the protocol for who gets what vaccine and when. It’s worth bearing this mental model in mind when you consider how projects can overstep the line and stray into areas of high risk and uncertainty. You need a way to frame the project and its drivers relative to these boundaries.

Project Risk Maturity (PRIMA) levels explained

Strategy is often framed in terms of how you win. But what does that mean? On large complex feats of engineering, you’re really competing against the clock—and against uncertainty. The same is also true for the vaccine program. To manage that uncertainty, you need to assess and mitigate your project’s risks. The better you are at this and the more frequently it’s done the more predictable a successful outcome becomes.

The government’s initial response to the pandemic felt a little like watching a couch potato realize they suddenly needed to get fit by running a marathon or taking on Everest. They just didn’t have the requisite baseline of fitness. This initial response back in March 2020 would indicate a PRIMA Level 1, making the whole outcome unpredictable. Or, you might say, a negative outcome became ever more predictable. But, of course, we’re not seeking failure.

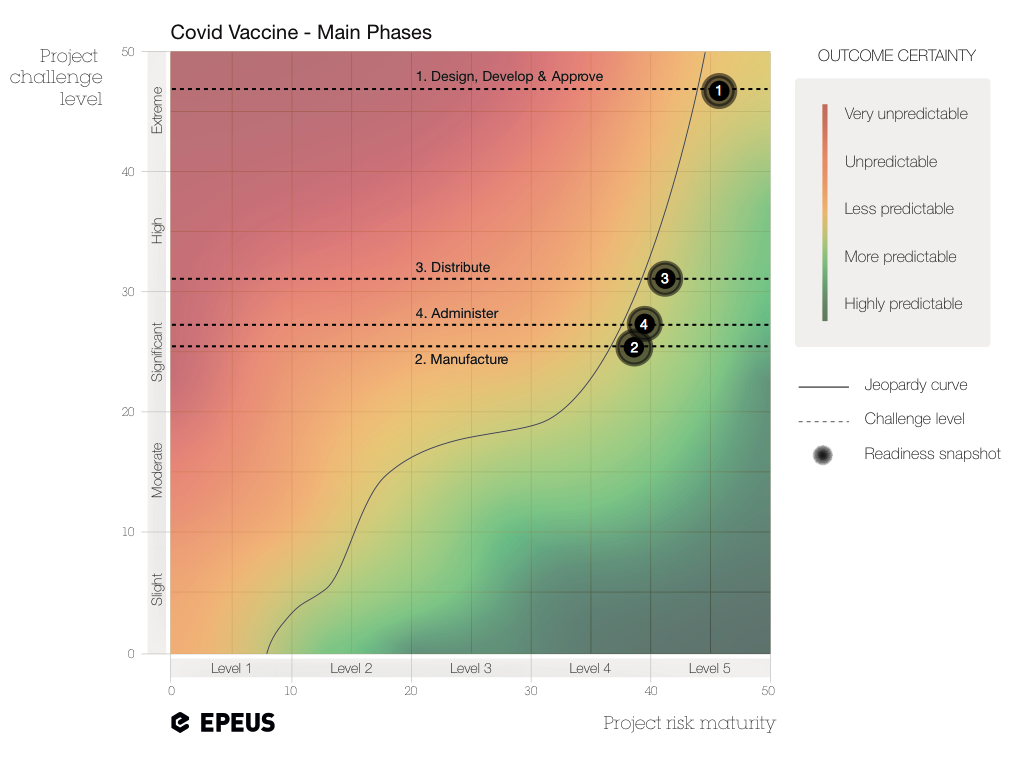

We define Project Risk Maturity (PRIMA) across five broad levels. Our Readiness Chart shows how different phases present different levels of challenge. We would expect to see this variation on any large complex project. Overall, for the vaccine rollout, we can see that the project organization would need a PRIMA Level 5 to make the project at all predictable. So what does that mean?

Many capability models use a staircase or building block metaphor to indicate the capabilities, standards and processes that must be in place. We believe these levels exist on a sliding scale; approaches are not relegated to discrete boxes. Some activities may appear at the lower levels but will likely not be as embedded or structured as at the more mature levels. Nonetheless, you have to draw the line somewhere and some indications for each level follow.

PRIMA Level 1: ‘Instinctive’

At this level, a project team would naturally ask ‘what if?’ on easily identifiable risks. But the process is rudimentary and finite; the team lacks a coherent approach. In the rollout, for example, would a place of worship acting as a vaccine station understand the risks associated with large volumes of people and the further spread of Covid? What kind of risk assessment would they do? What training would mitigate it? We also expect an overconfidence bias as people’s instinct is naturally towards easy solutions that don’t adequately account for complexity.

PRIMA Level 2: ‘Patchwork’

At Level 2, a project team would perform a risk assessment and develop a mitigation plan. But the approach is haphazard. People develop their own heuristics, which may increase their own status in the organization but often don’t translate into practices everyone can follow. This can lead to the ‘Frankenstein approach’ where people bring along their ‘best practices’ from previous organizations without properly adapting them to the current project. Such processes are internalized, based on knowledge and input from inside the organization, with little benchmarking from the wider industry.

PRIMA Level 3: ‘Competent’

Now, the project team brings in more of a risk-based strategy, meaning that the whole project starts to be considered in terms of ongoing risks, rather than a one-shot risk register completed early on to comply with regulations. We’d expect to start seeing more formalized scenario planning, the use of quantitative risk analysis tools (such as Pertmaster) and more ‘mindful’ approaches to ongoing operational risks from everyone involved. But this is likely still a standard ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to the project, rather than tailored to this specific context. We would expect to see risk managers here, but the wider organization may feel that ‘risk identification and mitigation’ is the risk management team’s job, not their own. Or, at least, there may not be a means of sharing and amplifying weak signals of risk to the people who can respond to them.

PRIMA Level 4: ‘Coherent’

Here we would see evidence of proper risk mapping with the goal of adding resilience at all phases. We would expect an analysis of Peak PRM (more on this in the next article), as well as far more stakeholder participation in risk identification and management. The project organization would actively seek out resources in the wider world to inform its decisions. The entire strategy and management of the project is seen in terms of risk (with commercial, legal, financial and other risks feeding into that). And risk identification and mitigation would happen much earlier in the project before risks become issues.

While in Level 2, people might talk about doing Monte Carlo simulations, at Level 3 they actually do them at some point. While at Level 4, they’re a standard part of the toolkit used at various points as the project progresses.

Level 5: ‘Resilient’

The team now has everything in the previous four levels. Windows of opportunity are considered, as well as threats. The long view, which considers project milestones, is balanced by short lookaheads (or ‘inch stones’ in Bent Flyvbjerg’s memorable phrase). And there are clear processes in place for escalating issues, utilizing specialists, recovery planning and more. Rather than the ‘get it done at all costs’ bravado of what we call ‘heroic endeavour’, the project team exudes an air of ‘professional endeavour’.

Essentially, at Level 5 you’re maximizing your knowledge inputs before the project starts, with Peak PRM baked into the strategy. Then, as the project continues, the team takes a mindful approach to risks, sensing and safeguarding as a whole group, rather than outsourcing that role to the ‘risk manager’.

Levers to pull to increase predictability

The ‘jeopardy curve’ represents a fuzzy boundary between greater and lesser predictability. If the assessment places your project on the wrong side of the line, you really only have two main levers to pull: decrease the overall challenge level, or increase your project risk maturity. Either approach can help you get over the line.

We discussed the key variables that define a project’s challenge level in part one of this series. It’s hard, or impossible, to reduce the level of innovation (ie, whether or not the project has been done before). But if someone else has done it before, or if they are familiar with the technical difficulties or certain building blocks of the project, you should consider bringing that experience on board.

This is what seemed to happen with the UK Government’s approach by creating the Vaccine Task Force under Chief Scientific Advisor Patrick Vallance, who, according to Bloomberg.com, ‘recognized that the government needed private-sector expertise [and] tapped Kate Bingham, a biochemist and venture capitalist who’d worked for 30 years with the pharmaceutical industry, and Clive Dix, who has a PhD in pharmacology and more than 20 years of industry experience’.

You might also consider reducing the scope, especially considering the geographical footprint. Whether authority is centralized or decentralized is also important. We’ve found that the number of external interfaces involved, and how they’re managed, plays an outsized role in the project’s complexity and therefore predictability. With the vaccine rollout, for example, the UK government allowed GPs to place orders directly with drug companies. This decentralized approach created fewer interfaces for the government project team. The Scottish Parliament, however, took a centralized approach with GPs having to place orders to the government itself. Each way has its risks with potential for bottlenecks. How interfaces are organized and managed will be key. Clarity of communication is vital.

The most obvious way to reduce a challenge on a project is to make it less tightly coupled, giving your team more time overall. The ability to respond when things start to veer off course as risks start to manifest is what brings resilience—the ability to recover. We’ll visit these topics in future articles. What’s clear with the vaccine rollout is that time is in short supply. So it will remain a tightly coupled project, with ever-present risks of crossing any of the three failure boundaries.

‘Project resilience’ over ‘organizational resilience’

The other lever to pull to increase the predictability of the project is to raise the level of project risk maturity (PRIMA). That means addressing the elements in the various levels above (an indicative, rather than exhaustive, list).

The key thing to note is that PRIMA should relate to a specific project and to the project team. You don’t need to increase your overall organizational resilience. We believe that transformational organizational change is not only unnecessary but counterproductive. It’s a long, expensive process to take a whole organization up every rung of the ladder in a maturity model. On a one-off project representing a large upside but considerable operational and reputational risk, you don’t have time to laboriously ascend to the mountaintop. You want to get to project resilience in one leap.

This means properly assessing the challenge and your key areas of vulnerability. But also bringing in outside specialists who can help during those periods. The UK Government’s dramatic shift in capability indicates they have taken this springboard approach, jumping to the PRIMA Level needed to achieve a successful outcome. Apart from the biochemist experts mentioned above, the Vaccine Task Force may turn to other expert organizations outside the usual channels, such as the Army, FedEx, Royal Mail or Amazon, each of whom has capabilities in logistics that the project might need.

Time will tell if the Vaccine Task Force is able to manage the risks as the project rolls out. It should be obvious, though, that the Government does not need to maintain this level of project risk maturity forever. It only applies to the specific challenges of this specific project. It’s too expensive and unnecessary to build in such organizational resilience. To deliver the project, and secure their reputation after the early stumbles, the Government needs project resilience that will maximize project value. We hope their momentum continues.

In the next article, we’ll look at the six core areas that comprise project risk maturity.

Read the other articles in the series:

» Part 1: Assessing the Challenge

» Part 2: Comparing challenge levels across phases

» Part 3: Elements of project risk maturity

___________________________________________

If you like this article, sign up for The Readiness Review: fresh insights for managing risk on energy projects, every Thursday.

Learn more about our Foresight Services for risk management.

___________________________________________