Managing risks on large complex projects

PART 2: Comparing challenge levels across phases

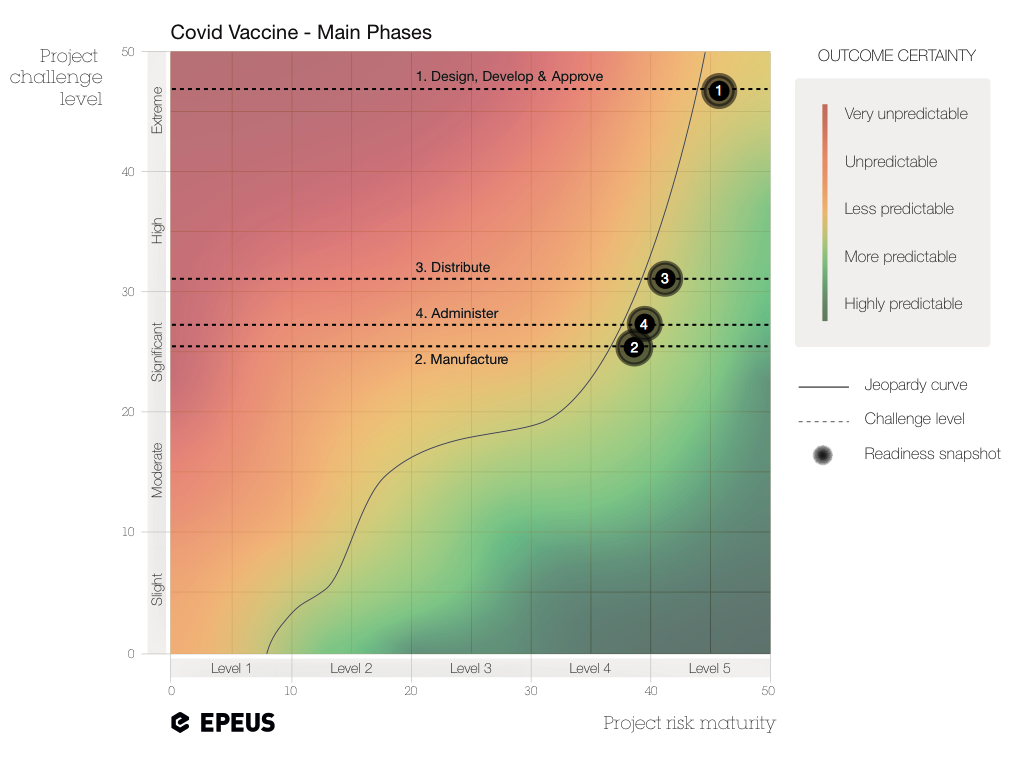

Leaders who want to maximize their project profits need to find the right level of project risk maturity to match the project challenge. The ‘jeopardy curve’ offers a visual way to assess if a project team and stakeholders have what it takes to achieve it.

In Part One of this article series, we introduced a range of factors that combine to create the level of the project challenge. Here, we’re going to use the Covid vaccine rollout—a project we all have a personal stake in—to see how these factors start to play out in terms of risk. The rollout has four main project phases: Design, Make, Distribute, Administer.

As I wrote before, we have no involvement in this project and are not trying to second-guess the government’s approach. But we can make some estimates on the variables that go into making the project challenge, which include things like innovation, technical difficulty and geographical spread (for more, see previous article). With these estimates, based on public-domain information about the current situation, we can then see what kind of project risk maturity we would expect the project to need.

At a glance, the chart indicates that the overall vaccine programme is ‘highly challenging’, and not necessarily the ‘extreme challenge’ that the word ‘unprecedented’ might lead us to believe. This is good news, of course. But why might it be the case? Let’s take a look at each phase.

Before we do, though, it’s worth noting that any large complex project usually has a key driver, whether of cost, time or quality. This leads to tradeoffs; pick any two and the third will be affected. Some projects, such as constructing an Olympic stadium, have a predefined end-date that can’t be exceeded, while others, like R&D projects, are measured above all on quality (at least ‘meeting spec’).

In the case of the vaccine rollout, quality is a given (ie, the vaccine has to work with minimal adverse effects). And we would expect time to be most important—getting the vaccine into the population with all due speed. Nonetheless, costs can vary wildly when you consider the millions of doses as well as the logistics involved. As the National Audit Office (NAO) states in its 2020 report on Lessons Learned on Major Programmes, ‘Organisations can face pressures from the outset to try and find programme savings, sometimes known as “efficiencies”, particularly when the government wants to make a programme more affordable alongside other spending commitments’. This temptation to push costs down carries its own risks as we’ll see below. Elevating the focus on cost may lead to basing decisions on the wrong overarching driver—or not fully understanding the conflict of interests—which can affect the predictability of the outcome, and the outcome itself.

(1) Design-Develop-Approve phase [challenge level: EXTREME]

Not surprisingly, this phase was an extreme challenge for the drug companies, largely due to the large number of management interfaces, compressed timescales and the fact that it was, at least initially, a research and development project (R&D) with no guarantee of success. However, as the project progressed and the focus shifted to testing, the project started to resemble one we might recognize in our world of large complex feats of engineering.

We know that the design and development of a vaccine was successful, but a recap on some of the aspects of this project provides an insight into the needed project risk maturity (PRM) level of the overall organisation. These drug companies should be Level 5 PRM because of the heavily regulated nature of the business. (We’ll explain more about the PRM levels in the next article).

Moreover, they develop medicines and vaccines as their core business. These organizations are familiar with the process and understand what risks they face to verify and validate that a medicine is safe. Nonetheless, firms such as Pfizer, AstraZeneca and Moderna would have had to enhance their processes to match the urgency of the context, recognizing that their usual one-size-fits-all approach wouldn’t be quick enough.

Interestingly, the Oxford-AstraZeneca group had already used ChAdOx1 vaccine technology to produce candidate vaccines against a number of pathogens including flu, Zika and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), another coronavirus. This was one case where the project was fortunate. But most large complex projects do, in fact, include building blocks that may successfully transfer from one project to the next.

(2) Manufacture phase [challenge level: SIGNIFICANT]

The actual process of making vaccines is well understood and would normally not present any challenge at all. It’s simply business as usual. In this case, though, the scale of the job, requiring millions of doses per week, creates a significant challenge. The project organization, led by the government, identified the regulatory approval process as a potential bottleneck. They enhanced their approach to engage with the regulators parallel to the vaccine development, as data from the trials became available. This is a good example of favouring project risk maturity over project process compliance. While the established process was complied with, it was adapted and enhanced to reflect the requirements of the project’s specific context.

The other main approach was to order 100 million doses so that manufacturing could proceed at scale prior to final regulatory approval. This was a risky decision at the time, given that the design efficacy of the vaccine was not fully validated. The approach, however, may be recognizable to those involved in large complex energy projects, when a decision is often taken to press on with fabrication before the design has completed its sometimes lengthy regulatory, or independently verified, approval process.

This measure mitigated the risk of gaining approval and then encountering a slow ramp-up to manufacturing doses, which would have delayed the overall rollout. If the vaccine had proved ineffective, a heavy political price would have been paid for such a decision. This is an example of placing ‘project value’ ahead of ‘political aspirations’, as we discussed in the first article of this series. You might instead view this as a calculated political risk which, if it worked, would show the government in a very positive light and bring a shine back to their tarnished reputation.

Interestingly, as I write this, news reports are focusing on how France and Germany also tried to place orders before trials were complete but their governments were overruled by the European Commission which wanted to secure 300 million doses for the whole bloc. At the time of writing, though, that target figure is in doubt. Meanwhile, the CEO of AstraZeneca, Pascal Soriot, accused the EU of getting ‘emotional’ about their delays in receiving vaccines, noting that the UK had profited by negotiating its contract with the company three months before Brussels. It seems that this phase has high potential for political gamesmanship as the EU threatens to block exports of Pfizer’s vaccine, made in Belgium, which may threaten Britain’s rollout schedule.

(3) Distribute phase [challenge level: HIGH]

This is where it gets challenging for the project owner, the UK government. National Health Service (NHS) organizations, such as Public Health England or Public Health Scotland, must decide how to get the vaccines into the hands of those capable of administering them across the land.

In the initial rollout, nine vulnerable categories were identified. Groups one to five are the same categories of people for which the annual flu vaccine is offered, including frontline health workers. In the 2019-20 flu season, 14 million adults and children were vaccinated. The first nine categories for the Covid vaccine come to 32 million people. Viewed through this lens, the rollout, though unprecedented, looks achievable. However, the sheer numbers involved, plus the need for two doses, rather than the single shot for flu, will increase the technical challenge. The government’s promised time targets also increase the tightness of the rollout, reducing the amount of time available to intervene and resolve issues and impacts.

We’re all familiar with the term ‘fast-tracked’ as a euphemism for heroic failure. The slack, or buffer, built into the project plan has arguably the greatest effect on the challenge level of a project. After all, with enough time to intervene when something goes wrong, you can usually overcome obstacles, although there’s often an unwanted cost impact. With this project so tightly coupled to a timeframe of ‘as soon as possible’, the need to detect risks early, adapt to changing circumstances and resolve issues without resorting to reactive management increases adds to the overall challenge level.

On the other hand, as the rollout progresses into the general public (ie, to all age groups) the programme becomes more repetitive and initial issues will be overcome. Increased knowledge and familiarity will inform overall efficiency. This has the counterintuitive effect of reducing the scale of challenge even as the numbers requiring vaccination increase dramatically.

(4) Administer phase [challenge level: SIGNIFICANT]

This is challenging because of the millions who need vaccinations, a problem we’ve already touched on with the distribution phase. The options for getting injections into people’s arms include the ‘hub approach’ where large centres are used to get through many vaccinations per day. These may be places of worship or leisure centres, which are currently unusable but which have the space needed. Alternatively, there’s the ‘thousand small ships’ approach, which in England would use the network of 11,000 community pharmacies. In this way, the required 2m per week could be handled with only 25 vaccinations per day handled by each pharmacy. Of course, in practice, the project will use a hybrid approach. But both scenarios require careful mitigation.

People need to be socially distanced (or you risk the prevention causing greater infection) and also need a 15-minute rest after the jab in case of any adverse reactions. This means that logistical issues, such as the available space for chairs, might be the constraint rather than stocks of the vaccine itself. And, of course, the project needs to recruit and train vaccinators and include enough redundancy to cope with inevitable variation.

Also, as I write this, the UK government is talking about ‘constraints on supply’. According to The Times, ‘GP-led vaccination centres that have vaccinated most of their over-80s patients have complained that their deliveries are being cut next week to allow other areas to catch up’. This may very well be a sensible move for the project as a whole, if the groups most at risk nationwide can get vaccinated even if these early areas have to wait a week or two to give the next groups their shots. But if anxieties are stoked around delays, the project team’s reputation can suffer and there’s a risk that poor decisions, and unforced errors, can result.

In our world of large complex feats of engineering, this kind of local optimization can show up when a workstream has achieved its targets and come in under budget. The manager of that workstream often tries to hang onto the budget as contingency, even if another workstream could use the money now to keep itself on track. This is why people at the top need to listen to those at ground level but still keep their own focus on the project as a whole.

‘Senior decision-makers should be alert to behaviours that suggest a schedule is becoming increasingly challenging,’ states the NAO again. ‘Persistent schedule replanning, the removal of scope and/or benefits, previously unplanned staging of a programme and excessive focus on individual project risks are signs that they need to examine closely the feasibility of the schedule.’ We’ll address this more in the next article as we look at how to sense, respond and adapt to risks as they emerge.

*

You can see that the challenges across all phases require a PRM Level 4-5. Only at this level do you develop a consistent ability to deal with the inherent complexity of the project to a point where negative impacts become manageable. Of course, the jeopardy curve is just a representation of an abstract idea. In complex projects, nothing is entirely predictable, nor wholly unpredictable. But the Readiness Chart helps stakeholders keep in mind the necessary level of resilience as they try to stay to the right of the line.

You may start to formulate your own idea of whether the whole project organization for the vaccine rollout is operating at a high enough PRM level. As I wrote before, though, we’re not trying to throw stones at the government. We’re just using the rollout to illustrate the kind of risk areas such complex projects encounter.

In the next article, we’ll look at some of the principles and tactics that can increase your own PRM level.

Read the other articles in the series:

» Part 1: Assessing the Challenge

» Part 2: Comparing challenge levels across phases

» Part 3: Elements of project risk maturity

___________________________________________

If you like this article, sign up for The Readiness Review: fresh insights for managing risk on energy projects, every Thursday.

Learn more about our Foresight Services for risk management.

___________________________________________