The perils of butterfly collecting

‘Of course, learning lessons from each project is vital.’ Any project manager will tell you that. But what lessons are they really learning?

In our experience, few organizations are as effective at knowledge capture and transfer as they imagine. While they may, as part of their project governance approach, collect observations around general matters like ‘what worked well’ and ‘what didn’t work so well’, they get stuck at the ‘capture’ stage.

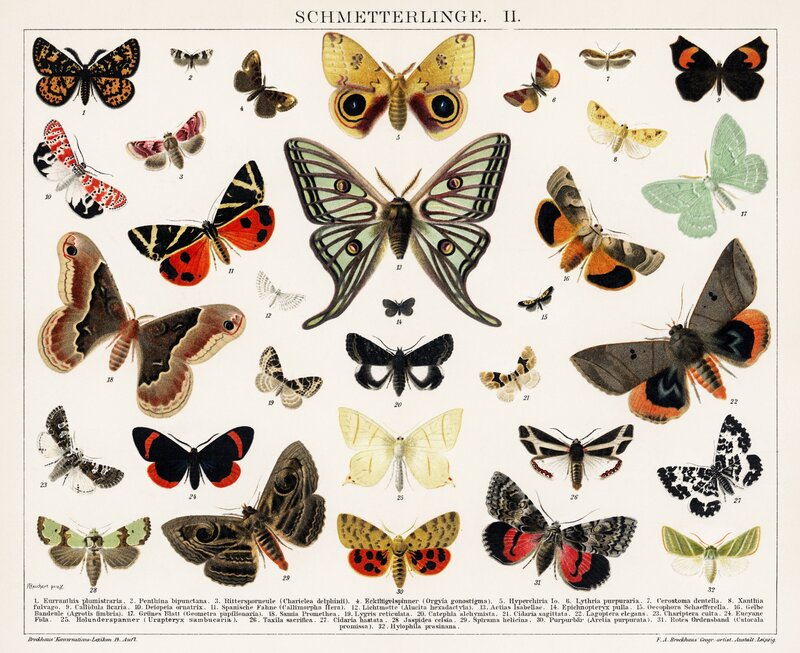

Knowledge capture mostly happens around project closeout, so-called ‘after-action reviews’, when minds are either focused on boxing up the job to pass to operations, or demobbing personnel. The image that springs to mind is of Victorian gentleman butterfly collectors vigorously waving large nets over wildflower meadows. They do catch all manner of things. But how are the specimens identified? And which are important or worthy of further study?

Too often, captured ‘lessons’ are fed back into ‘project central’ where, just like at the museum, they are pinned. Only a small proportion are placed on display, chosen by the curator, to catch casual glances of fleeting interested parties. The rest are consigned to the dusty recesses of the project archives.

I’m no lepidopterist, but on visits to natural history museums one can’t help but admire the sheer diversity of butterfly species. Project mishaps are not quite as numerous. But divorced from their habitat—the project’s context—it’s hard for those who follow to make sense of them.

As individual humans, we are hardwired to learn. But collective learning is hard. If all you’re doing is capturing, the people involved on the job may learn, jolted by the reminder of an event they’d put behind them. But those left rummaging in a repository won’t have that context. The passage of time dulls the understanding; the significance is lost.

“As individual humans, we are hardwired to learn. But collective learning is hard”

So how can we improve how insights are transferred to the next project?

A typical Project Management Office would look for patterns, identifying outputs and inputs, then seek to update procedures. But most of the stuff that goes wrong isn’t so amenable to improvement. Instead, we recommend what we call Peak PRM (Project Risk Management).

Every complex project is unique in some way. To account for this specific context means doing qualitative risk evaluation in the earliest stages. Peak PRM takes inputs from academic studies, from different industries, and, yes, from your own recent projects. The best opportunity for learning is when events are fresh, which means not leaving them till a rushed ‘washup’ of half-recollections at the end.

“Every complex project is unique in some way”

Instead, capture observations as you go as stories. This has many benefits. Anecdotes are how people share information anyway. They naturally give the vital context for whatever happened. They are ‘sticky’ and memorable and more likely to be read or—even better—heard. Get people in the habit of recording themselves on their phone right after the event with an audio memo. Gather and tag the files each week. Then, at the closeout stage, you can catalogue the stories for relevance and retrieval at the closeout stage.

Finally, the Peak PRM process sorts the rare specimens from the garden variety. Teams often overestimate the likelihood of a risk occurring or not, leading to either unnecessary project overhead for risks which will almost certainly not occur, or lack of mitigation for those that might. With multiple inputs to Peak PRM, and an understanding of prior and current context, you can make more informed decisions—and have more successful projects.