For offshore wind, aspirations threaten profits

As offshore wind demands ever-larger turbines, are the players gambling too much to satisfy their aspirations? Two views of the same project, from owner and contractor, highlight their different perceptions of risk. Who’s right?

A recent BBC report highlighted how offshore wind is pushing manufacturers to supersize their wind turbines, creating a race that may be unwinnable. ‘If you look at the financial results of the [manufacturers], basically none of us make money anymore,’ said Aurélie Nasse, head of offshore product market strategy at Vestas, a Danish wind turbine manufacturer working on a massive prototype. ‘That’s a big risk.’

We agree, but let’s tug on that thread a little. Clearly, everyone is making money but probably not much profit. Scaling offshore wind energy to the desired output requires massive turbines, requiring bigger ships and equipment to transport and install them. The heavy costs associated with such large complex feats of engineering make profit margins tight, so it only takes one or two nasty surprises to erode profits—or eradicate them completely.

Across upstream energy sectors, project owners always look to offload as much risk as they can onto their supply chain. Those jostling for contracts do so with their eyes wide open; or they should. But the apparent confidence of each player, and their risk profile, has serious implications for project success.

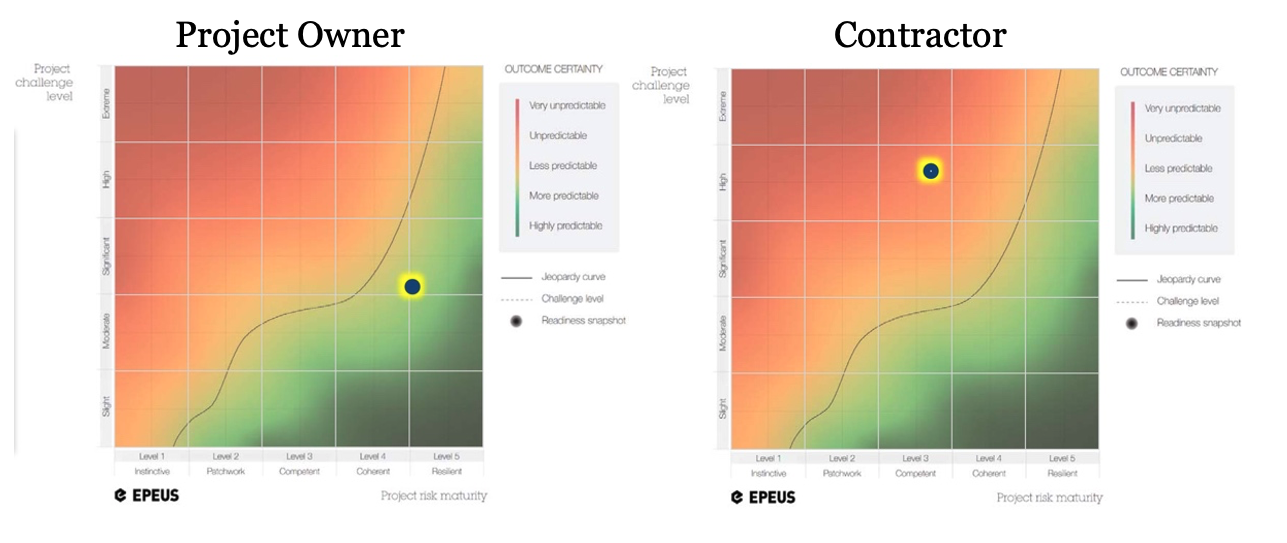

These charts, taken from Project Horizons, our self-appraisal software, show two views of the same large offshore wind energy project, captured within weeks of each other.

Tellingly, both parties view the project’s challenge level differently. For the project owner, it’s a ‘moderate-to-significant challenge’; the contractor, undertaking only part the project, views its own scope as ‘highly challenging’. What’s going on here?

The project owner sees themselves in a good place, with a more predictable project outcome. The contractor’s results, however, indicate unpredictability and a lack of confidence in meeting their own expectations at the time the contract was awarded. It appears the project team is exposed to a lot of uncertainty without being well-equipped to deal with it.

Some caveats: This comparison is illustrative and is only one assessment, albeit the project director’s view. To get a more accurate snapshot, all project team members should take the assessment. But these results certainly align with the contracting strategy in terms of who’s feeling the heat.

Looking through too narrow a lens

Both parties are, of course, thinking of the project relative to their own organizational experiences. For the owner, the project is not too complex, because they’ve offloaded the complexity to their contractors. Clearly, though, the owner’s profits depend on the contractor coming through on time and on budget.

This brings us back to Ms Nasse’s point about not making any money and why that’s a big risk. The problem with working at the edge of current engineering capability is that prototypes themselves are designed to prove a concept, not make money. In Oil & Gas projects, we saw this time and again with, for example, floating production storage and offloading (FPSO) vessels. Each field operator would want to convert the topsides to the specific needs of the output from their wells, requiring modifications to the original design for that deployment, and further modifications for the one after that.

This desire to keep upping the ante on turbine blades may cause similar challenges. And, of course, as turbines get bigger, the whole support infrastructure needs to change to accommodate them, much as airports needed to adapt if they were going to accept Airbus’s behemoth A380. Uncoincidentally, production of the A380 will end in 2021, with Airbus losing money on each aircraft.

The arms race for ever-larger turbines is ostensibly driven by the expected benefits from economies of scale, including needing less undersea cabling for fewer turbines in total. It’s also surely driven by aspirations to build the biggest and best equipment. The success of both these drivers depends more directly on the contracting policies of the project owners.

Installing wind turbines should be a repeatable process, with the benefits that brings.

Only designing once (more or less) reduces the unique elements and therefore uncertainty. Changing the design of the turbines from one project to the next negates the gains from previous projects because each one becomes its own prototype. Is that really worth the gains from having fewer transmission lines? After all, the ocean is a big place.

And, as the scale of each piece of engineering increases, should the owner see the whole windfarm as ‘the project’? Or does each turbine—from manufacture to installation—become its own project, like delivering a single A380 aircraft? And, finally, what about all the work incurred after manufacture and installation?

Will they see each other in court?

The BBC article ends by stating that, while future engineering may allow for even more gigantic turbines, ‘it could be the practicalities and costs of installing, maintaining and operating them that really challenge their seemingly unstoppable growth in the future.’

Those constraints may be significant. But even now, as our Project Horizons snapshots indicate, there’s significant risk for the project if the players are not aligned on the level of the challenge and don’t have the capability to rise to it. So, who’s seeing things most clearly, the project owner or the contractor? The latter, we suspect. The solution is for them to increase their capability to deliver the project before time becomes the deciding factor.

For the project owner, an approach which places corporate aspiration over project profits is bad for business. If allowed to permeate a project’s ecosystem, it’s ultimately bad for getting the owner’s project profitably over the line.

When faced with the prospect of diminishing returns, those within the supply chain will often look to protect their own interests. They will, of course, do their utmost to deliver on their promises. But after all those avenues have been tried, the only road often open to clawing back some profits is the claims court.

________________________________

Can we help you?

Our Foresight and Oversight services are designed to help you deliver project success, even if the process is sometimes uncomfortable.

For a clearer view on your project’s challenge level and your team’s capability, try our self-appraisal software: Project Horizons

________________________________