Dangerous tensions hide in plain sight

A tram derailment that killed seven and injured dozens makes a key point about risk tragically clear.

‘It was something no one ever expected to happen,’ intones a Sky News reporter, ‘despite the fact there had been previous late-braking incidents at this exact spot. Including one just ten days before the accident’. That disconnect between ‘no one expected’ and the glaring string of near misses is jarring.

Another report on the accident’s court case mentioned that a ‘blind spot caused by the rail track’s design meant the train driver was oblivious to a risk that otherwise would have been obvious’.

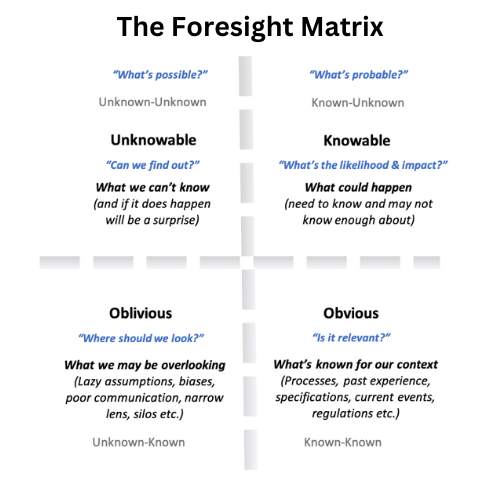

In our world of large complex projects, the gap between what’s known in advance and what’s left unknown makes all the difference to project delivery. The goal is to find everything knowable and obvious and not remain oblivious.

True unknown-unknowns do exist, of course. But so do unknown-knowns—things that should be obvious, or at least knowable, that are obscured by project organizational design failures of lazy assumptions, biases, silos, and the like. In our experience, these unknown-knowns are a key source of value-eroding events (AKA ‘risks’) on projects and which project management teams all-too-often remain oblivious.

“The goal is to find everything knowable and obvious and not remain oblivious.”

By way of illustration, we were recently asked to conduct a review of an overrunning construction project. The constructor (our client) suspected it had fallen foul of myriad delays caused by its customer failing to live up to its promises. The stakes were high, with impacts to the tune of $150 million with our client estimating many months’ worth of additional work to complete delivery. If their customer didn’t accept responsibility for causing the delay, the constructor was facing hefty, liquidated damages.

The fact that a customer’s actions (or lack thereof) can cause negative impacts to a contractor’s progress is so well known it should be obvious. So much so that situation management requirements—designed to protect a contractor from a client just doing what it wants—appear in most well written contracts. In this case, the contract was well written, and did indeed contain conditions which, if met, would allow for the impacts of any customer-caused delay to be reimbursed on an individual claim-by-claim basis.

Good intentions vs good process

As it turned out, our analysis showed that the delay was not the constructor’s fault. However, despite numerous delays and disruptive incidents, no corresponding individual claims had ever been made, leaving our client in a bit of a sticky, contractually exposed, situation.

With Covid and other complications making the project more challenging, the two parties had agreed to collaborate from the get-go to overcome potential difficulties. ‘The cart may not have any wheels but if we all pull and push together, we’ll get it up the hill’ sort of thing. They even penned a side agreement around collaboration which, among other things, sought to minimize change orders, deal with issues at a site level and generally work together to achieve the desired and expected project outcomes. Yet the raising of change orders was a requirement to claim for delays and disruption. And early and continuous escalation was necessary and required by the contract’s terms.

“The raising of change orders was a requirement to claim for delays and disruption”

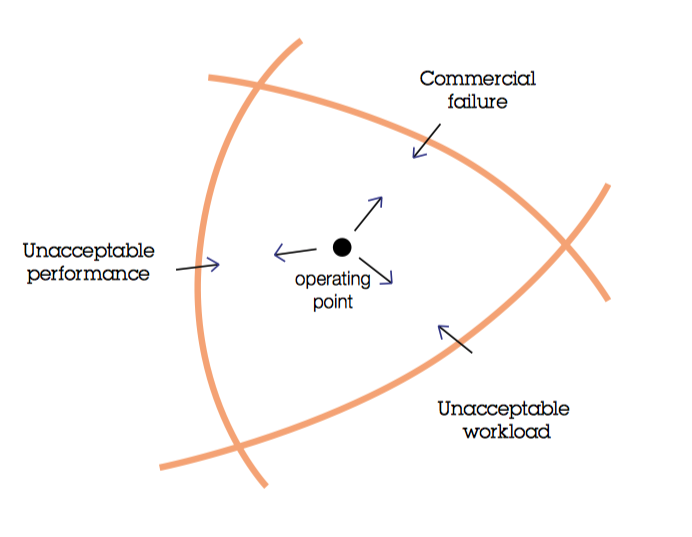

A collaborative approach is laudable, of course. But the project’s organizational design resulted in less formal project team behaviour while they all worked together to understand and resolve onsite situations. The absence of delay claims for individual events required by the parties’ contract meant both parties were operating beyond the failure boundary of required acceptable performance described, in part, within the contract.

Diagram of Failure Boundaries

So what?

As with the tram incident, the project’s collaborative organizational design a had created a blind spot. The project’s leaders were oblivious to a risk so obvious that provisions for dealing with it were in the contract in black and white. Just never implemented.

A mitigation process for a known risk (already in place and agreed) was therefore overlooked, or not recognized as important because the ‘just get the job done’ side agreement pushed the mitigation into obscurity. The chosen approach to the project and its organizational design exposed the contractor to large losses and created a weaker negotiating position when delays piled up.

Battle-hardened readers might be tempted to write off this anecdote as just another case of RTFC (read the effing contract). But the inclusion of these kinds of conditions goes further. The contract is designed to protect the interests of the contractor and its shareholders. So perhaps this meaning-behind-the-words was something else that remained in the ‘unknown-known’ quadrant of the Foresight Matrix.

Was there a happy ending? Yes. The independent analysis and insights we provided gave our client the means to confidently negotiate a resolution acceptable to both parties. A bit more detailed foresight, however, should have turned the ‘oblivious’ into the ‘obvious’, avoiding a situation that was fortunate not to become a train wreck.

________________________________

Can we help you?

Our Foresight and Oversight services are designed to help you deliver project success, even if the process is sometimes uncomfortable.

If you feel your project is stepping over a boundary, try our assessment tool: Project Horizons

________________________________

[Image credit: train tracks by Wolfgang Rottmann on Unsplash]