The quest for more predictable, and more profitable, projects

Managing large complex feats of engineering requires a different mindset to ‘business as usual’ operations. We offer three reasons why and suggest an approach to secure your profits and your reputation.

Do you want your project team to feel comfortable? Or do you want the project to succeed? We all want to enjoy our work, but projects involving large complex feats of engineering are never a walk in the park. Nor should they be. So how can we make large complex projects more predictable?

The 1980s brought the quality revolution to industrial environments, inspired by W Edwards Deming and Toyota, leading to Total Quality Management and Six Sigma. Then came the safety revolution, which saw eliminating injuries at work as a moral duty. It seems we’re still going through the project management revolution. But while it’s natural for executives to seek to learn from previous inflection points to stay ahead of the pack, are these revolutions relevant? And does a transformation around project management even make sense?

In ‘Roads to Resilience’, an excellent recent report from Cranfield School of Management, the authors quote managers of a power station, operated by Drax, who talk of cultivating a culture of ‘chronic unease’ around safety. This approach, influenced by renowned risk management expert Professor James Reason, is well suited to operating a power station and has helped Drax maintain an exemplary record.

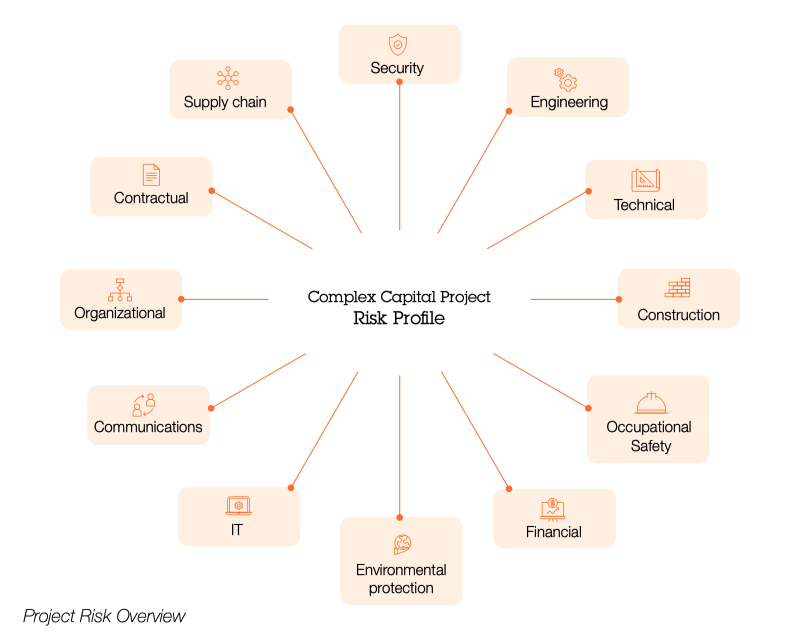

The notion of zero-harm safety culture, based on continuous improvement, has become a staple of corporate governance. It starts with the principle of early gains and requires a long-term commitment to education, process improvement, continuous measurement, and constant reinforcement. It’s a slow process. And while safety is vital, it’s just one element of your project risk profile (see graphic 1).

[Graphic 1: Project Risk Overview]

We believe it’s a mistake to try to apply the same kind of blanket provisions and companywide culture change that drive safety to all kinds of project risks. Three reasons stand out. First, every project is unique. Second, given it’s never been done quite like this, the project is uncertain. Third, a project is a temporary undertaking. Let’s look at the implications.

Every complex project is unique

Going back to safety as one risk, there’s good reason to try to bake a zero-tolerance approach to incidents into the culture. You look for near misses, for example, and consider how best to avoid them in future. This approach applies well to core operations that are repetitive. In upstream energy, the quest to eliminate accidents in drilling operations or offshore windfarm maintenance makes total sense. Of course, a ‘safety first’ culture also works to your advantage on projects. But it’s the wrong approach for managing the array of risks you face on a project which are not related to safety.

A large complex project always includes at least one unique element that removes it from business as usual. That might be the scale of the job, the geographical spread, climatic conditions, a change in delivery partner, or dozens of other variables.

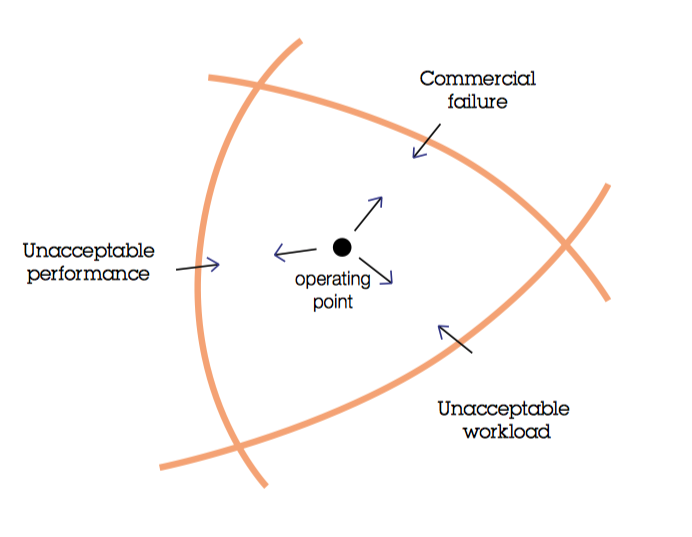

The Rasmussen model of staying within three boundaries is helpful here (see graphic 2). Accidents typically happen when people cross the ‘unacceptable workload’ boundary. But ‘unacceptable performance’ and ‘commercial failure’ are equally destructive to your project’s profits. These two boundaries impact share prices as much as a fatal accident or environmental disaster, even if the public doesn’t view them this way.

[Graphic 2: Diagram of Failure Boundaries]

Complex projects are uncertain

The Agile revolution arose to address the uncertainty of knowing all the requirements for software development before building the product. While software development definitely plays an ever-greater role in every industry, the complex projects we’re talking about here involve engineering that needs to work first time. You can’t have a minimum viable drilling rig and then iterate. Energy projects deal in waterfall plans and stage gates. The issues introduced by a project management office (PMO), however, are more subtle.

How do you make a standard system fit for purpose when the project is unique and uncertain? Perhaps 80% of known risks can be addressed by good corporate governance guidelines. But it’s the 20% not covered that can cost you dear. But try to anticipate every eventuality in your companywide handbook and the policies will become bloated, hard to understand and even harder to apply. The temptation to implement such an initiative is strong; leaders want to feel the organization is ready for anything. But it’s a false sense of security.

Managers who feel they have solid corporate standards for running projects can get complacent. Previous success is no guarantee of future success. To uncover all the known risks, you have to go wide and deep in your risk appraising and consider all the factors that make the undertaking unique. And by trying to account for 99% of eventualities, most of which won’t happen, each project becomes much more expensive than needed. And the 1% of unforeseen incidents that do occur will still come as a nasty surprise. This causes a double whammy to your project margins.

It also leads to the need for continuous improvement to the PMO. But do you really want to fold in mitigations from your latest project into future projects that will have a different context and may never be used again? That said, we don’t suggest you start from scratch for each project. We expect to see rules on every project, such as how you format and update your risk register, build and manage the budget, or ensure compliance with other functions. These and other aspects influence how you rough out the boundary of acceptable performance.

The place for companywide systems of governance is, for example, with financial and ethical rules that you always follow. The company leadership should also be assessing the significance of the project risk to the overall corporate risk profile and manage and control it accordingly. But for all the risks in the top graphic, the golden rule is ‘context is king’. Mitigation activities are driven by the risk analysis and what the project actually needs for it to succeed. Each should be viewed through the lens of the project, which makes it a temporary organization.

A project is a temporary organization

By now, it should be clear why we distinguish between the company’s permanent structure, functions and operations, and the ‘project organization’ which is, by nature, temporary. No central system can manage this. Management policies are designed to be inflexible (‘thou shalt…’). We’re seeking flexibility—project resilience rather than corporate robustness.

Think of each project as an organizational change initiative. You’ll keep certain aspects of how you do things, while introducing new measures for the duration of this project. The questions become: ‘What in our standard handbook is right for this new project’s context? What approach should we take? How should we design this project? And what areas of vulnerability do we need to enhance?’

That’s why we recommend a project-by-project approach for identifying and implementing improvement, enhanced to meet the specific needs of the undertaking. This allows you to be both ‘robust’—baking in enough mitigation activity to prevent known risks—and ‘resilient’, having enough flexibility in the system to sense the inevitable unknowable risks quickly enough to prevent them from materializing and to get quickly back on course after a setback.

Learning brings its own rewards

To return to James Reason and safety, the idea of ‘chronic unease’ may sound like an existential malady. And we agree that, when it comes to complex projects, the prevailing mood should be pragmatic pessimism rather than energetic optimism. But that doesn’t preclude a happy, engaged team. Quite the opposite. When people are on a shared mission, and are aware of the dangers ahead, they gain a spirit of camaraderie. And by being mindful of the dangers that lurk, they can more easily enter a state of psychological ‘flow’ where the challenge of the task is balanced by their capability to handle it.

Finally, we encourage our clients to look outside their immediate environment for inspiration. Why only learn from your own projects—both your mistakes and successes—when you can learn from those of so many others? When we join an engagement, for example, we bring the collective knowledge of almost 250 projects.

________________________________

Can we help you?

Our Foresight and Oversight services are designed to help you deliver project success, even if the process is sometimes uncomfortable.

If you feel your project is stepping over a boundary, try our assessment tool: Project Horizons

________________________________